Majestic Masses – November 2023

Program notes by Sanford Dole

Our group was founded in 1979 as the Baroque Choral Guild. As our performing repertoire grew to span all eras and styles, we changed to a more neutral name so as not to restrict what our audiences might expect of us, while still maintaining the BCG initials. That said, music of the 17th and 18th centuries has always been a staple and beloved part of our programming.

This season we are revisiting some of the core repertoire that has sustained us for the past 45 seasons. For this program, Icons of the Baroque, we return to the era of BCG’s original focus, from which I have selected two of my favorite works. While the music of Bach and Handel can rightly be referred to as iconic in any context, these particular pieces, Bach’s Jesu, meine Freude, and Handel’s Dixit Dominus, hold a special place in my heart. I first performed this music as a student in Berkeley High School’s Concert Chorale, and they influenced my decision, at age 16, to follow a path as a professional musician.

In addition to Bach and Handel we are presenting a charming work by a lesser-known composer of the Baroque era, Isabella Leonarda. More on her later.

This season we are revisiting some of the core repertoire that has sustained us for the past 45 seasons. For this program, Icons of the Baroque, we return to the era of BCG’s original focus, from which I have selected two of my favorite works. While the music of Bach and Handel can rightly be referred to as iconic in any context, these particular pieces, Bach’s Jesu, meine Freude, and Handel’s Dixit Dominus, hold a special place in my heart. I first performed this music as a student in Berkeley High School’s Concert Chorale, and they influenced my decision, at age 16, to follow a path as a professional musician.

In addition to Bach and Handel we are presenting a charming work by a lesser-known composer of the Baroque era, Isabella Leonarda. More on her later.

The apex of J. S Bach’s career came in the last 27 years of his life, when he was the director of music for the city of Leipzig and oversaw the music program at St. Thomas Church and its adjoining school. There he produced both the St. Matthew and St. John Passions, three complete cantata cycles, and at least five authenticated motets, not to mention the organ and instrumental music. Among his duties was the composition of music for special civic occasions, such as the funerals of prominent citizens. His motets were likely created for such events. While they are often sung unaccompanied, historically informed performances take into account that in Bach’s time it was customary to support the voices with basso continuo (harpsichord or small organ) and instruments playing colla parte (doubling the vocal lines).

Though the motets are fewer in number than his cantatas, they constitute some of the most daring and impressive music ever conceived for vocal ensemble. We do know that, on the special occasions for which he wrote his motets, Bach had greater resources at his disposal than for a usual Sunday church service. Because of that, he was able to hire more skilled singers for these affairs. Some of his motets are in eight parts, usually double choir, and include more complex counterpoint. Some scholars have suggested that they were used for training the students at the Thomasschule, but the skills required makes this seem unlikely.

Jesu, meine Freude (Jesus, my joy) is a special case, however. Recent scholarship suggests that this work was compiled from pre-existing material, as was the Credo from his monumental Mass in B minor. It is a funeral motet; indeed, some scholars believe Bach intended it for himself. Its exceptional length and carefully plotted symmetry suggest that Jesu, meine Freude had special meaning for the composer. Its eleven movements, composed for three-, four-, and five-part chorus, intersperse the six stanzas of Johann Franck’s 1653 hymn of the same name with texts from the 8th chapter of Paul’s Letter to the Romans. The hymn is written in the first person and deals with a believer’s bond to Jesus, who is addressed as a helper in physical and spiritual distress, and therefore a reason for joy. Paul’s biblical letter invokes the believer’s wished-for release from pride, glory, and other earthly temptations. Taken together these ideas encapsulate the core of Lutheran teachings.

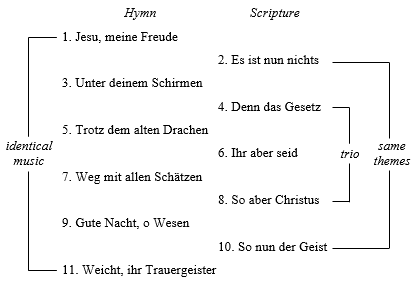

What I find most satisfying, as a lover of balance and symmetry, is the exquisite way the motet is constructed. The hymn tune, composed by Johann Crüger, is harmonized in various ways during the odd-numbered movements. The text from Romans is set in the even-numbered movements. The work unfolds as a musical palindrome centered around the central 5-part fugue in the sixth movement, Ihr aber seid nicht fleischlich (But ye are not in the flesh). On either side of this are two groups (nos. 3–5 and nos. 7–9) that contain a chorale, a trio, and an aria-like movement. Number 10 is a recap of number 2, and numbers 1 and 11 use identical music.

Though the motets are fewer in number than his cantatas, they constitute some of the most daring and impressive music ever conceived for vocal ensemble. We do know that, on the special occasions for which he wrote his motets, Bach had greater resources at his disposal than for a usual Sunday church service. Because of that, he was able to hire more skilled singers for these affairs. Some of his motets are in eight parts, usually double choir, and include more complex counterpoint. Some scholars have suggested that they were used for training the students at the Thomasschule, but the skills required makes this seem unlikely.

Jesu, meine Freude (Jesus, my joy) is a special case, however. Recent scholarship suggests that this work was compiled from pre-existing material, as was the Credo from his monumental Mass in B minor. It is a funeral motet; indeed, some scholars believe Bach intended it for himself. Its exceptional length and carefully plotted symmetry suggest that Jesu, meine Freude had special meaning for the composer. Its eleven movements, composed for three-, four-, and five-part chorus, intersperse the six stanzas of Johann Franck’s 1653 hymn of the same name with texts from the 8th chapter of Paul’s Letter to the Romans. The hymn is written in the first person and deals with a believer’s bond to Jesus, who is addressed as a helper in physical and spiritual distress, and therefore a reason for joy. Paul’s biblical letter invokes the believer’s wished-for release from pride, glory, and other earthly temptations. Taken together these ideas encapsulate the core of Lutheran teachings.

What I find most satisfying, as a lover of balance and symmetry, is the exquisite way the motet is constructed. The hymn tune, composed by Johann Crüger, is harmonized in various ways during the odd-numbered movements. The text from Romans is set in the even-numbered movements. The work unfolds as a musical palindrome centered around the central 5-part fugue in the sixth movement, Ihr aber seid nicht fleischlich (But ye are not in the flesh). On either side of this are two groups (nos. 3–5 and nos. 7–9) that contain a chorale, a trio, and an aria-like movement. Number 10 is a recap of number 2, and numbers 1 and 11 use identical music.

In addition to its symmetry, Jesu, meine Freude is striking for the strength and clarity of its word painting. You can hear this, for example, in the rests after “nichts” (nothing) and in the vivid setting of “tobe, Welt, und springe” (rage, world, and shatter). Bach depicts walking (“wandeln”) by long melismas that proceed at a steady gait, sometimes imitative, with one voice repeating after another. Passages such as these, remarks the scholar Hans-Joachim Marx, reveal Bach as a profound “musicus poeticus” who was attempting to move, entertain and instruct his audience.

I first discovered Isabella Leonarda when researching a program of women composers we presented in 2019. She was born in the Italian city of Novara (west of Milan) into an old and prominent Novarese family whose members included important church and civic officials. Her father was a well-heeled lawyer who held the title of count.

At age 16, Leonarda entered the Collegio di Sant’Orsola (Convent of St. Ursula), where she stayed for the remainder of her life. Over the next 60 years she rose in the order to become mother superior and later provincial mother superior. She was also identified in documents as a music teacher, suggesting that Leonarda played some role within the convent teaching the other nuns to perform music. This role may have also afforded her opportunities for the performance of her works by the convent’s sisters.

Not much is known about Leonarda’s musical education before entering Sant’Orsola, though many speculate that she may have had some such education due to the high social and economic status of her family. It has also been suggested that once in the convent, she studied with Gasparo Casati (1610–1641), a talented but little-known composer who was maestro di cappella at the Novara cathedral from 1635 until his death.

While Leonarda was a highly regarded composer in her home city, she was apparently little known in other parts of Italy. Her first compositions, two motets for two voices, appeared in Casati’s Third Book of Sacred Concerts, making her the first known woman composer to be published. During the second half of the century she published over 200 works in 20 collections of her own. It appears that she was over the age of 50 before she started composing regularly, and it was at that time that she began publishing the works that we know her for today. Leonarda’s works include examples of nearly every sacred genre: motets and sacred concertos for one to four voices, sacred Latin dialogues, psalm settings, responsories, Magnificats, litanies, masses. In addition, she wrote a few secular songs and a large number of sonatas.

The Magnificat comes from a collection published in 1698. It is scored for four-part choir, continuo, and two obbligato violins. We don’t know if this work was conceived for use by the sisters at Sant’Orsola. If so, the mixed-voice setting may represent an adaption for publication, as the printed volumes were intended for the general market of choirs of men and boys. Evidence exists that despite a ban on the use of instruments in convents, the Lombard nuns played trombones, an excellent choice for the lower voices.

At age 16, Leonarda entered the Collegio di Sant’Orsola (Convent of St. Ursula), where she stayed for the remainder of her life. Over the next 60 years she rose in the order to become mother superior and later provincial mother superior. She was also identified in documents as a music teacher, suggesting that Leonarda played some role within the convent teaching the other nuns to perform music. This role may have also afforded her opportunities for the performance of her works by the convent’s sisters.

Not much is known about Leonarda’s musical education before entering Sant’Orsola, though many speculate that she may have had some such education due to the high social and economic status of her family. It has also been suggested that once in the convent, she studied with Gasparo Casati (1610–1641), a talented but little-known composer who was maestro di cappella at the Novara cathedral from 1635 until his death.

While Leonarda was a highly regarded composer in her home city, she was apparently little known in other parts of Italy. Her first compositions, two motets for two voices, appeared in Casati’s Third Book of Sacred Concerts, making her the first known woman composer to be published. During the second half of the century she published over 200 works in 20 collections of her own. It appears that she was over the age of 50 before she started composing regularly, and it was at that time that she began publishing the works that we know her for today. Leonarda’s works include examples of nearly every sacred genre: motets and sacred concertos for one to four voices, sacred Latin dialogues, psalm settings, responsories, Magnificats, litanies, masses. In addition, she wrote a few secular songs and a large number of sonatas.

The Magnificat comes from a collection published in 1698. It is scored for four-part choir, continuo, and two obbligato violins. We don’t know if this work was conceived for use by the sisters at Sant’Orsola. If so, the mixed-voice setting may represent an adaption for publication, as the printed volumes were intended for the general market of choirs of men and boys. Evidence exists that despite a ban on the use of instruments in convents, the Lombard nuns played trombones, an excellent choice for the lower voices.

Born and educated in Halle, George Frideric Handel moved to Hamburg in his late teens, where his prodigious talent was evident in his early operas produced there. But the young composer knew he needed to travel to Italy, the birthplace of opera, to further his writing skills and connections. Ironically, he discovered that in Rome at the time there was a Papal ban on the performance of opera. While he did travel to Florence and Naples and do some operatic writing in these years, a lot of his energy was spent writing sacred music.

Despite being a Lutheran, Handel, as an ambitious and clever young man, was somehow able to gain the patronage of three Cardinals while in Rome. Dixit Dominus is a setting of Psalm 110 that Handel composed in 1707. Along with other Latin psalm settings and motets composed at about the same time, it very probably formed part of a setting of the Carmelite Vespers for the feast of the Madonna del Carmine. The 22-year-old Handel, having already proven himself a master of counterpoint during his North German “apprenticeship,” added a facility for expressive melody and lively Corelli-style instrumental writing during this Italian “journeyman” phase of his career.

Dixit Dominus is resplendent with bright color, vocal virtuosity, expansive structure, and driving energy. Clearly it was designed by Handel to demonstrate his ability to write in the Italian style, and it has marked resonances with the choral works of Vivaldi. John Eliot Gardiner has suggested that it was “almost as though this young composer, newly arrived in the land of virtuoso singers and players, was daring his hosts to greater and greater feats of virtuosity.”

Handel sets the vivid images of the psalm text in the form of a cantata in ten movements for five-part chorus, soloists, strings, and continuo. After the energetic opening chorus comes a simple and elegant alto solo, followed by a beautifully lyrical movement for soprano, built on a repeated triplet figure. The drama resumes in the fourth movement, “Juravit Dominus,” one of alternating slow and fast sections. The slow sections are notable for their daring chromatic harmony and bold dissonances. The sixth movement combines verses 5 and 6 of the psalm text. The unmistakable influence of Corelli can be heard in the instrumental introduction, with the two violin parts and later the voices constantly overlapping in a series of striking suspensions. The ensuing section, “Judicabit in nationibus,” is a busy fugato which appropriately disintegrates at the word “ruinas.” There follows one of the most remarkable passages in this unique work: a series of percussive chords repeated to the same syllable (a device very reminiscent of Monteverdi) in the word conquassabit, graphically depicting a crushing military victory. The final “Gloria Patri” brings back material from the opening chorus, this time with even more brilliant figuration, and closes the work with an extended and superbly executed fugue.

The choral writing is virtuosic throughout, described by H. C. Robbins Landon as “of staggering technical difficulty, displaying immediately the excellence of Roman choirs at the beginning of the century.”

We hope you enjoy these Icons of the Baroque and look forward to seeing you for our next program, American Journey, on June 1st and 2nd. Those concerts will travel through the eras and styles of American music from William Billings to Leonard Bernstein and beyond. Moving from colonial New England to Hollywood, we’ll visit the heartland and the Old West, campfires, concert halls, jazz clubs, and Broadway theaters along the way.

Despite being a Lutheran, Handel, as an ambitious and clever young man, was somehow able to gain the patronage of three Cardinals while in Rome. Dixit Dominus is a setting of Psalm 110 that Handel composed in 1707. Along with other Latin psalm settings and motets composed at about the same time, it very probably formed part of a setting of the Carmelite Vespers for the feast of the Madonna del Carmine. The 22-year-old Handel, having already proven himself a master of counterpoint during his North German “apprenticeship,” added a facility for expressive melody and lively Corelli-style instrumental writing during this Italian “journeyman” phase of his career.

Dixit Dominus is resplendent with bright color, vocal virtuosity, expansive structure, and driving energy. Clearly it was designed by Handel to demonstrate his ability to write in the Italian style, and it has marked resonances with the choral works of Vivaldi. John Eliot Gardiner has suggested that it was “almost as though this young composer, newly arrived in the land of virtuoso singers and players, was daring his hosts to greater and greater feats of virtuosity.”

Handel sets the vivid images of the psalm text in the form of a cantata in ten movements for five-part chorus, soloists, strings, and continuo. After the energetic opening chorus comes a simple and elegant alto solo, followed by a beautifully lyrical movement for soprano, built on a repeated triplet figure. The drama resumes in the fourth movement, “Juravit Dominus,” one of alternating slow and fast sections. The slow sections are notable for their daring chromatic harmony and bold dissonances. The sixth movement combines verses 5 and 6 of the psalm text. The unmistakable influence of Corelli can be heard in the instrumental introduction, with the two violin parts and later the voices constantly overlapping in a series of striking suspensions. The ensuing section, “Judicabit in nationibus,” is a busy fugato which appropriately disintegrates at the word “ruinas.” There follows one of the most remarkable passages in this unique work: a series of percussive chords repeated to the same syllable (a device very reminiscent of Monteverdi) in the word conquassabit, graphically depicting a crushing military victory. The final “Gloria Patri” brings back material from the opening chorus, this time with even more brilliant figuration, and closes the work with an extended and superbly executed fugue.

The choral writing is virtuosic throughout, described by H. C. Robbins Landon as “of staggering technical difficulty, displaying immediately the excellence of Roman choirs at the beginning of the century.”

We hope you enjoy these Icons of the Baroque and look forward to seeing you for our next program, American Journey, on June 1st and 2nd. Those concerts will travel through the eras and styles of American music from William Billings to Leonard Bernstein and beyond. Moving from colonial New England to Hollywood, we’ll visit the heartland and the Old West, campfires, concert halls, jazz clubs, and Broadway theaters along the way.